Site visit to Forsyth’s in Rothes, Speyside. Potty about Copper! – Scotch Whisky News

Site visit to Forsyth’s in Rothes, Speyside. Potty about Copper!

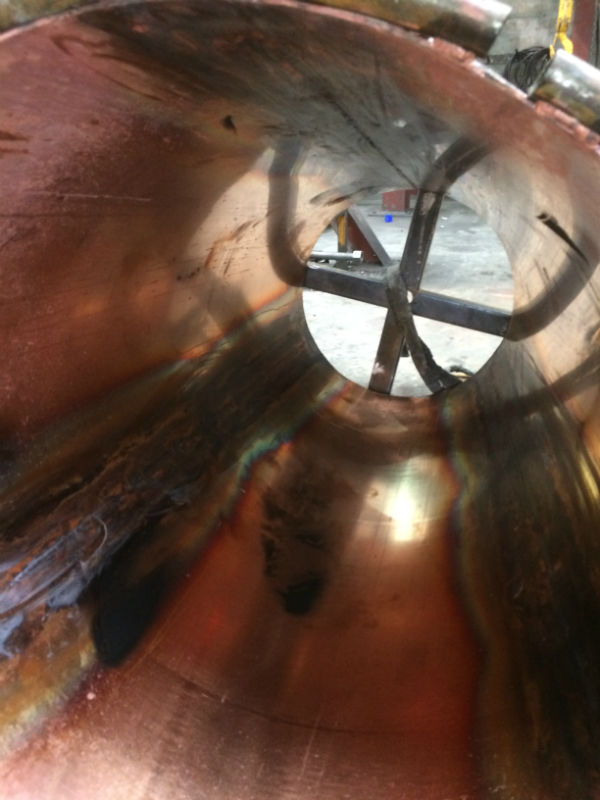

I was lucky enough to tour the Rothes plant with Ingvar Ronde and was amazed at what I saw! Copper everywhere, flat and made up ready to go, bits for stills and pipes all over the place, this company is really busy, so thanks to them for allowing us in to spoil their day … I could have stayed there all day taking photos every few minutes, with items wrapped and labelled going around the world, or just up the road to Glenfiddich, also a pile destined for my local area, to Lindores distillery (I will be there soon). Aye you can see my photos, obviously I am no in them as I took them! Thanks go to Forsyth’s and Ingvar’s group. This was just one visit on a packed itinerary for Ingvar, on tour with us again. More blogs will follow re the whole tour.

Alexander Forsyth served his time as a coppersmith in Rothes in the 1890’s. The owner of the brass and copperworks at the time was Robert Willison. After finishing his apprenticeship Alexander remained with Willison as a tradesman and then foreman until 1933. It was at this point that he bought the business from the retiring Willison. Forsyth and Son was born. The son was Ernest (better known as “Toot”) and after returning from service in the Second World War he took over the running of the business. Toot quickly introduced new welding techniques to replace the traditional riveting process which helped keep the business moving with times.Today fourth generation Richard Ernest carries on the mantle as Managing Director.

Their engineers have experience in the process design of pot and column still plants, mashing to final distillation. During the design phase they can size plant, specify equipment, produce flow schematics and P&ID’s, size piping and specify automation as required, all handcrafted and hand shaped pots to any contour or size that clients desire. In the last 20 years Forsyths have been exporting all over the globe – pots from 50L to 25,000L charge capacity using direct flame firing, steam coil, steam jacket, electric element or electric hotplate as the heat source, still heads in any shape with the main three styles being ogee, lamp glass and boil ball all of which are finished with a sweeping swan neck. Their two main areas of business are the oil and gas industries. Typical fabrications include structural steelwork, piping, pressure vessels, umbilical/pipe reels and tanks. Alcoholic industries (we know them for better I think) from the supply of distillation equipment only to turnkey distillery design and build, plant upgrade or expansion projects.

Distilleries take great pride in their stills, no two have the same shape or size. But why? Is there more to their design than meets the eye? The Whisky Professor tells all. Does size matter? the shape and size of a still has a significant effect on the character of the spirit being produced – and it is all to do with copper. Copper was first used to make stills because it is malleable and can be worked into shape easily. This longer the contact between vapour and copper, the lighter the spirit will be. A taller still is more likely to produce a light spirit – hello Glenmorangie – the tallest stills in Scotland, with long necks measuring nearly 17 feet high. They say only the lightest and purest vapors make it all the way up and out. A smaller still is more likely to make a heavy spirit because that conversation is a short one. Think Macallan. The angle of the lyne arm also has an impact. If it points upwards that copper contact and reflux is extended. A downward-angled lyne arm stops the contact in its tracks and helps to gather robust flavours. Distillers choose the shape of the still and manage the way it is run in order to produce the distillery’s unique character. One of the things Forsyth’s offer is a design service, they offer many types, size and shape of still to the client, who then can pick and mix to design their own unique still. So, shape does matter, Macallan have small stills – 3,900 litres, they believe the shape offers rich, fruity characteristics.

The difference between pot stills and column stills is that pot stills operate on a batch by batch basis, while column stills are/cab be continuously. With column distillation, the mash enters near the top of the still and begins flowing downward bringing it closer to the heating source, once heated enough to evaporate the vapor rises up through plates. At each plate the vapor ends up leaving behind some of its heavier compounds. Most pot stills are made entirely from copper, column stills may be part stainless steel.

Did I enjoy my visit to Forsyth’s? Aye, can you no tell?

Paul McLean, on tour with Ingvar Ronde, Scotland, May 2017