A NOTE ON CAMPBELTOWN AND THE DISTILLING TRADE

by Hedley G Wright M.A

The Royal Burgh of Campbeltown is situated at the south end of the Kintyre Peninsula, that long strip of Argyll which divides the Firth of Clyde from the Atlantic Ocean and from where the back gardens of Ireland can be distinguished with binoculars on any clear washing day. In A.D. 503 at Dalruadhain, later called Ceann Loch Cille Chairian and finally Campbeltown, Fergus established the parliament of the minute Celtic kingdom of the Scots of which he was the first King. It could hardly have been anticipated that he was to found a monarchy whose domains were to extend in time to cover all present-day Scotland, Great Britain and eventually large portions of the then unknown world: Contemporary successors of Fergus are crowned whilst seated on that same Stone of Destiny from which he ruled his unruly little territories. St Columba lived here or three years teaching Christianity for the first time on Scottish soil before he sailed to the Isle of Iona 1,400 years ago to within a few months. It was from Campbeltown that Flora MacDonald sailed with her family for American in 1774, after having played her historic part in the closing chapters of the ’45 rebellion of “Bonnie Prince Charlie”. In Campbeltown, Exciseman Robert Burns wooed his “Sweet Highland Mary” at a time when the small burgh was a centre of Scotch Whisky distilling.

The Scots have distilled Whisky here from the earliest times, for the drink is a Celtic one and the skill of manufacture was a common property of the Western Highlander and the Irishman. The first written account of Whisky from this area is, however, quite late, in 1591, and it is in the records of the “Pursmaister” of the Thane (or Laird) of Cawdor: “In Taylone (a village about 15 miles from Campbeltown) in September of 1591 – deliueret to Makconchie Stronechormicheis man same day that brocht the aquavytie vis viij d.”

Shortly afterwards occurred the most important event in the history of Scotch Whisky: the Statutes of the Icolmkill (1609): in order to combat the ill effects of the behaviour of the Western Highlanders of imported Wines and Spirits only the consumption of home made drink was permitted. This resulted in giving Scotch Whisky such a boost that its fame spread to the rest of Scotland as also did the traditions for making it. In the same year the first licence to produce Whisky commercially in Campbeltown was awarded to John Boyll.

Private distilling was not seriously tampered with till 1779 when the capacity of private stills was reduced by law from ten gallons to two gallons. Two years later private distilling was declared illegal. Licensed commercial distilling was then subjected to increasing taxation which discriminated against the Campbeltown distillers compared with their East Highland and Lowland competitors so that in 1797 legal distilling was not worth the trouble: this was the date of the last licence in Campbeltown for 20 years. It is as well to add that in the following three years 292 illicit stills were seized and destroyed by the authorities in Campbeltown. Having killed their golden goose the Westminster Government tried several negative an unsuccessful attempts at artificial respiration and it was only when they reduced the duty to 9s. 41/2d. per gallon that the first legal distillery in Campbeltown was restarted: a further drastic reduction in duty in 1823 made legal distilling competitive against “smuggling” and then began the golden days of the Campbeltown distillers.

A complete list of the Campbeltown distilleries with the date of the construction of the “official” plant is:

1817 Campbeltown Distillery 1830 Lochside Distillery

1823 Kinloch Distillery 1831 Kintyre Distillery

1824 Meadowburn Distillery 1832 Dalintober Distillery

1824 Longrow Distillery 1832 Caledonian Distillery

1824 Lochhead Distillery 1832 Scotia Distillery

1825 Dalaruan Distillery 1833 Lochruan Distillery

1825 Hazelburn Distillery 1834 Mountain Dew Distillery

1825 Burnside Distillery (originally Thistle Distillery)

1825 Rieclachan Distillery 1834 Drumore Distillery

1826 Union Distillery 1834 Toberanrigh Distillery

1827 Glenramskill Distillery 1834 Glenside Distillery

1827 Highland Distillery 1835 Mossfield Distillery

1828 McKinnon’s Argyll Distillery 1844 Albyn Distillery

1828 Springbank Distillery 1844 Argyll Distillery

1828 Name Unknown 1868 Benmore Distillery

(Messrs Campbell, McFarlane & Harvey) 1872 Glengyle Distillery

1830 Springside Distillery 1877 Glen Nevis Distillery

1830 Name Unknown 1879 Ardlussa Distillery

(Messrs Andrew & Montgomery)

The Campbeltown distillers were quickly able to corner the Glasgow market, a city with which there had been a good smuggling trade, and thereby ensure the pre-eminence of Campbeltown amongst the other distilling areas of Scotland. In 1897, 1,810,226 gallons of Whisky were made in Campbeltown alone. Success, however, contained the seeds of destruction and a startling change overtook the trade in the earlier portion of the present century. There are probably several causes of the ensuing decline of the Campbeltown distilleries. Speculators bought large quantities of Whisky causing overproduction which not only led to their own ruin but also the ruin of several distillers (is there a present day lesson here?)

Furthermore, it is feared that during the times of plenty some distillers, confident of their Glasgow monopoly, became careless and produced inferior Spirit which they filled into poor-quality casks. The result was that Whiskies once known by such phrases as “The Hector of the West” and “The Deepest Bourdon of the Choir” gained the description of “Stinking Fish”. It is true that the distilleries which made such poor Spirit were the first to fail but in their fall they dragged almost the whole Campbeltown trade with them. The economic depression of the 1920s and ’30s reduced the drinking capacity of Glasgow so greatly as to emphasise overpoweringly the overproduction of previous years.

The East and Central Highland distillers were quick to make an entry into Glasgow and by the early 1930s had almost completely displaced the Campbeltown giants. Only one distillery managed to survive the economic depression and the indiscriminate condemnation of Campbeltown Whisky: another distillery, after lying dormant for some years, was able to restart trading under new ownership. These two distilleries, Springbank and Scotia (renamed Glen Scotia), are the only two survivors of the 34 built in former years. Although many of the warehouses of the old distilleries are still in use for various purposes there is nothing left of the plant and little or nothing of the distillery buildings themselves; only here and there the crumbling shell of a still-house or tun-room reminds the Campbeltown people of their century-long boom.

Springbank and Glen Scotia have succeeded in overcoming the former Campbeltown stigma and are appreciated and used by most blending houses, large and small. The even, centre-of-the-palate flavour which made the Campbeltowns so famous in the early days is considered by some to be indispensable in knitting together the many components of a modern blend. It remains to be seen whether over the years the Campbeltown will again resume its dominance of the Whisky trade.

Scotch Whisky Distillers of to-day

Springbank Distillery is situated in the heart of Campbeltown and the premises to-day, comprise not only the original buildings of 1828, but also parts of the extinct distilleries of Longrow, Rieclachan, Union, Springside and Argyll. It was originally the fourteenth distillery to be built in the golden days of the early 19th century but is now the senior and larger of the two remaining distilleries. It is in the nearly unique position of being the only distillery left in Scotland which is exclusively owned and controlled by the original family of distillers.

The story of the Mitchell family is in a way a history of recent Campbeltown distilling and it is impossible to give an account of Springbank Distillery without mentioning several of the other distilleries of old Campbeltown.

Local records suggest that the Mitchell family came to Argyll with the second wave of Lowland settlement about 1660. Many of the family were maltsters and, in the pre-Jacobite days, it must be assumed that they were also distillers. Some Mitchells were a little more colourful, for instance James Mitchell, a weaver in Campbeltown, was a rebel in the Marquis of Argyle’s rising in support of Monmouth in 1685, but his error was counterbalanced by other members of the family, James and Archibald Mitchell, another Archibald and his son Robert, who in 1692, are recorded as being Fencible Men of Argyle: in other words they were members of the Home Guard of those times.

The history of the Springbank Distillery can be conveniently begun with Archibald Mitchell (1734-1818) a farmer near Campbeltown and the great-great-grandfather of the distillery’s present managing director. Archibald’s sister married Hugh Ferguson, a maltster in Campbeltown and his son, Archibald (II), married this sister’s daughter: so it is not surprising that Archibald (II) traded as a maltster, the business of his uncle/father-in-law. Archibald (II)’s malt barns were on the site of the future Springbank Distillery and were indeed to become the original maltings of the distillery.

Although it is known from the private ledger of a local coppersmith that Archibald operated a still for Whisky, he never troubled to put himself on the right side of the law by taking out a license: it was left to his sons, Hugh, Archibald (III) John and William and one of his daughters, Mary, to bring themselves within the law. Archibald (III) was one of the original partners of Rieclachan Distillery (1825) where he was later joined by his brother Hugh. Springbank Distillery was built on the site of Archibald (II)’s illegal distillery in 1828, by the Reid family who were the in-laws of the Mitchells but, as the Reids soon found themselves in financial trouble, John and William Mitchell bought the property in 1837 and thereby restored their father’s distillery to the direct line of descent. The new and legal firm of J. and W. Mitchell made their first sale on 14th November, 1837, to one, Isebela Brown of Campbeltown, who bought 24 gallons at 8s. 5d per gallon. This price included the government duty; the present price of a proof gallon of new Springbank Whisky is £12 7s. 5d. inclusive of duty! Not all the new firm’s customers were to disappear into obscurity like Isebela Brown: during the first year’s trading, on 8th October, 1838, John Walker of Kilmarnock, bought 112 gallons at 8s. 8d. per gallon and all the world knows that this John Walker is “still going strong”. Samuel Dow of Glasgow, who made an earlier purchase on 12th March, 1838, is another well-known name in the trade that has survived through the years.

However, trouble lay ahead, for John and William, who were farmers as well as distillers, quarrelled violently, not about Whisky but about sheep. William left Springbank to join his brothers at Rieclachan, so John took his own son into partnership and thus changed the firm’s name to J. and A. Mitchell which it still remains. It should be noticed that William was not content to rest in partnership with his Rieclachan brothers for, in 1872, he started Glengyle Distillery as sole proprietor. Neither, for that matter, did John remain satisfied with Springbank and, in 1851, he was one of three partners that bought out Toberanrigh Distillery which had been built by his cousin, Alexander Wylie, in 1834.

Mary Mitchell, daughter of Archibald (II) and now a widow, was one of four partners of Templeton, Fulton & Co., who built Drumore Distillery in 1834. In this way did the Mitchells establish their position among the other distilling magnates in Campbeltown: the Colvilles, the Fergusons, and the Mactaggarts, to name a few.

Springbank Distillery prospered and in 1897, when the firm became a limited company, it was one of the largest in Campbeltown. Springbank, although affected adversely by the depression of the 1920s and ’30s, fortunately managed to avoid the wave of prejudice that built up against Campbeltown whiskies at about the same time and it is probably due to this alone that the company managed to survive that difficult period. It is interesting to note that in September, 1924, when White Horse Distillers applied for a rates reduction on their recently acquired Hazelburn Distillery in Campbeltown, evidence was given to the court that the market price for Ardbeg (Islay) Whisky was 18s. 3d., for Craigellachie (Highland) 16s. and for Hazelburn 8s.; furthermore, Hazelburn had only worked 10 periods during the previous year in place of the normal 50. Springbank was fortunate in having a full year’s production at that time: but what of the other Mitchell distilleries? Both Drumore and Toberanrigh were already closed and Glengyle had just been sold for £300! It was only a matter of time before Rieclachan was caught up by economic conditions and, although it produced probably the finest of the Campbeltown Whiskies, the business was wound up. An interesting souvenir from the period of growing Campbeltown disfavour remains in the warehouses of Springbank in the form of a hogshead of 1919 Whisky: it is a fine clean tasting spirit without any trace of woodiness which might have been gained by the use of a poor cask: it will be kept for another seven years before bottling.

Springbank Distillery to-day has changed in several features from older times. The company has been one of the pioneers in mechanisation within the distilling industry and the movement of barley and malt is now performed entirely be belts, screws and elevators. The barley intake of the distillery was adapted several years ago for the receipt of bulk supplies and anticipated considerably the method of transport and delivery that is now becoming popular.

The actual maltings have been rationalised so that there is only one set of floors and one kiln where formerly there had been two independent maltings. Modern techniques of box or drum maltings were rejected in favour of the traditional system as they did not effect an adequate economy to compensate for the poorer quality of malt produced by these methods. The green malt is dried on a pressure kiln of modern design and this item of equipment has been found to give a superior quality of malt and also effect considerable economy of time and fuel.

The peat used to dry the malt is cut within a few miles of the distillery by the company itself. Springbank can manufacture all its malt requirements and is one of the few distilleries in Scotland that can do this. The dried malt is stored in metal bins before being ground into a course flour or “grist”. The grist is mashed with hot water in a large iron and copper tun of conventional type and the resulting sweet solution, the “wort”, is strained away from the undissolved malt husks, the “draff”, and is cooled by passing through a Paraflow heat exchanger and run into the fermenting vessels, the “wash-backs”. The unwanted draff is a high quality cattle food and is sold entirely to local farmers. The actual wash-backs are made of Scottish “boat skin” larch wood, for it is the belief of the proprietors that a steel wash-back, although less expensive to install and maintain, gives a distinct taint to the final Whisky, in an analogous manner to the distinctive tone given to a violin by the use of steel strings. In the wash-back yeast is added to the worts which then ferment to become a sour Beer-like liquid called wash.

From this stage onwards operations are acutely watched by officers of H.M. Customs and Excise to ensure that no alcohol goes into consumption without payment of duty. The wash is pumped into a large copper still which is heated underneath and also, simultaneously, by an internal coil through which superheated steam is passed.

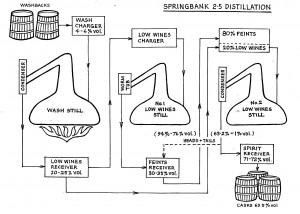

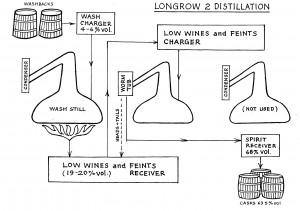

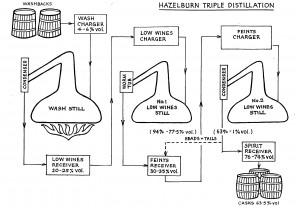

This method of heating a wash-still is the traditional Campbeltown technique and has been used at Springbank for as long as memory and records indicate; it is thought that no distilleries outside Campbeltown use this method. The hot vapours that are driven off the wash are condensed again by passing them through a long coiled “worm” of copper tube which is cooled with running water. When all the alcohol has been driven off the wash, distillation is stopped and the alcohol free “pot ale” remaining in the still is run to waste. The collected distillate, known as the low-Wines, is carefully divided into two portions, one of which is distilled again in a small “doubling still” to give “feints” which are mixed with the remaining low-Wines and run into a third still where the final distillation takes place. A large portion of the Spirit condensed in the final distillation is rejected and it is only an accurately controlled “middle cut” that is run into the Spirit store for filling the customers’ casks.

In spite of the mechanisation that has taken place in recent years all the vital processes in the manufacture of Springbank Whisky have remained unaltered so the actual quantity of Whisky produced to-day is only slightly greater than at the beginning of the century. The water used for malting, mashing and cooling all comes from the Crosshill Loch which lies on the outskirts of “Whisky City” about one mile from the distillery.

Article written in the early nineteen sixties by Mr. Hedley G. Wright, the head of the family firm which owns the distillery. He is directly descended from the Mitchells.